Tron (1982) Directed by Steven Lisberger. Screenplay by Steven Lisberger based on a story by Steven Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird. Starring Jeff Bridges, Bruce Boxleitner, David Warner, Cindy Morgan, and Barnard Hughes.

Let’s do a little time warp and cast ourselves back to 1982. Ronald Reagan is president of the United States. Margaret Thatcher is prime minister of the United Kingdom. Argentina occupies the Falkland Islands in a failed attempt to wrest them from British control. Steven Spielberg’s E.T. is released and becomes the most successful movie in the world for the next decade. Michael Jackson’s Thriller is released and becomes the most successful album of all time. Israel invades Lebanon. In Chicago a never-identified murderer slips potassium cyanide into Tylenol capsules and kills seven people. Sony begins selling the world’s first consumer compact disc player. The population of China surpasses one billion.

And Time makes an unexpected choice for Man of the Year: the computer.

Roger Rosenblatt’s cover article for that issue of Time is a truly bizarre glimpse into the past. You should definitely read it. It’s somehow exactly what you would imagine a Time “Machine of the Year” piece from the early ’80s to be. Computers! Newfangled gadgets coming to change the world! Personal computers had been available in various forms for some time, but it was only in the late ’70s and early ’80s that they began to go truly mainstream. There was a massive cultural shift happening, and it’s no surprise that it would be reflected in cinema—both in subject matter and in how movies were made.

When we’re talking about movies, it’s important to clarify what we mean when we say a film is influential. It might mean that a movie was wildly popular upon release and spawned numerous knock-offs and mimics, or it might mean that a movie altered the art and craft of filmmaking or the business of moviemaking. Tron is in the latter category, but it also sits in an odd place in film history.

It wasn’t actually the first film to use computer-generated imagery (CGI) with live-action scenes (that was Westworld, in 1973), but it did very much demonstrate what CGI could do with a lot of work and an expansive imagination. But nobody has ever really tried to make anything like it. Not until they made the sequel, that is. Sure, there were films and TV shows that borrowed elements of the visual style, and everybody gets obsessed with sentient computers now and then, but Tron is the only movie like Tron. It doesn’t quite fit into this month’s film club theme, although it’s a commonly cited influence for a lot of virtual reality films, but it doesn’t fit anywhere else either, and I wanted to talk about it, so here we are.

Tron’s uniqueness is a rare thing in Hollywood, and it’s even more rare because we’re talking about a mainstream film from a significant studio. In 1982, Disney wasn’t anywhere near the cultural juggernaut it is today, but it was still making movies that people watched and liked. Tron wasn’t what anybody expected from Disney; even though the critical response was favorable and it found a respectable audience, it ended up as a financial disappointment. This wasn’t helped by the fact that it came out the same summer as E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark, Poltergeist, and Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan. There were flashy special effects and big, successful genre movies everywhere in theaters in the summer of 1982. (Tron did better than Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner but worse than Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits. I don’t know what that says about cinematic trends in 1982. Draw your own conclusions.)

Steven Lisberger got the idea for Tron in 1976 when he encountered Pong, one of the earliest video games ever created. He already had an interest in animation, and he began thinking about how animation could be used to visualize computers and computer games. He spent a few years developing the idea with his business partner, Donald Kushner, before they began shopping it around Hollywood. This led to the project being mentioned in Variety, which caught the attention of computer scientist Alan Kay, who was working at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) at the time, developing a few little things like, oh, you know, object-oriented programming, graphical user interfaces, the progenitor of modern laptop and tablet computers, and so on. In between all of that work revolutionizing technology and changing the world forever, Kay also found time to persuade Lisberger to use computer-generated images in his planned movie.

(A quick aside for a sweet Hollywood story: During the development of the film, Kay met Bonnie MacBird, who wrote the first several drafts of the Tron script using Kay as inspiration for the character Alan Bradley. In typical Hollywood fashion, multiple rewrites, numerous contributors, and a credits dispute means MacBird is credited for the story but not the screenplay. But throughout all this, MacBird and Kay fell in love and eventually married. They’re still married today.)

Several studios passed on the project. In another timeline or another era, Disney might have passed on it too, but Disney in the early ’80s was going through a bit of a rough patch. Walt Disney had died in 1966, and the company waffled around for a while, not quite sure what to do in his absence. They were producing movies through the 1970s, and many of those films were quite successful (including the 1973 animated feature Robin Hood, which for decades has been responsible for confused tweens developing romantic crushes on a fox). But they were shedding talent (in 1977 Don Bluth and eleven other animators left to form their own company) and films from other companies were getting a lot more hype (e.g., Star Wars). By the time Lisberger and Kushner brought their movie treatment to Disney, the studio wanted something bold and splashy and science fictional.

But they first wanted Lisberger and Kushner to prove they could do it, because the movie would require a heck of a lot of money and use some unfamiliar and unproven techniques. There was some trial and error before they settled on the combination of techniques that make up the final film. The first plan was for all the scenes in the computer world to be animated, but Lisberger and the film’s special effects supervisor, Richard Taylor, decided instead to combine live-action shots with a technique called backlight animation. (Not the Wētā Workshop Richard Taylor. Different Richard Taylor entirely.)

This gets a bit complicated, but it’s also really cool, so bear with me as we take a little field trip into animation school.

In backlight animation, a scene is first photographed normally, except that areas meant to glow brightly and vibrantly are blacked out. Then the scene is photographed again, this time with a counter-matte masking everything except those blacked-out areas, to create a transparency of the scene. Then light is shone through the transparency to be photographed yet again. The light is often modified to achieve the desired effect, using colored gels, filters, meshes, or changing exposure. That’s how animated films from the era created fire and lightning effects, among other things, because it allows for a bright, brilliant element to stand out from the rest of the animation. Don Bluth’s The Secret of NIMH (1982), for example, has some truly beautiful uses of backlight animation.

But Lisberger and Taylor figured that was too easy, I guess, so they decided to add several layers of complexity by combining the animation technique with live-action scenes—and to do it not just for emphasis in a few key scenes, but in every single scene that takes place in the computer world.

Their first idea was to film the actors in gray suits against an all-white background, but cinematographer Bruce Logan (who had worked on the special effects of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars) convinced them that wasn’t going to work, so they switched to filming the actors in white suits against an all-black background. The white costumes had solid black lines all over them to later be transformed into those distinctive glowing stripes. The scenes were filmed in black and white on 65mm negatives because, quite simply, the more standard 35mm format was just not large enough for what they required. (There were so few working 65mm cameras in Hollywood at the time, the production staff would tell stories about working around missing parts and broken viewfinders.)

The next step was to blow up those 65mm negatives onto large-format Kodalith film, on which everything that was not going to glow (most importantly: the actors’ faces) had to be manually blacked out before the backlight was applied. Because there were so many colors involved, each scene required numerous passes with different filters; some scenes required as many as 50 photographic passes. Then, because everything was filmed against a solid black studio, the characters had to be rotoscoped out and placed against the desired background. The backgrounds are mostly matte paintings—there are some 300 in the film—which get their glow-y, high-tech look from colored filters and light.

The key word here is manually. All of this had to be done by hand. Every single frame of every single scene that shows the actors in the computer world, amounting to about 50 minutes of the movie’s 96-minute runtime. It required truckloads of film and other materials and literally hundreds of post-production staff.

It is—let’s be frank—a completely fucking insane way to make a movie. Don’t get me wrong: it looks great. It is a genuinely brilliant and eye-catching way to create a wholly unfamiliar computer environment. But it’s also no wonder that nobody ever tried anything like it again.

The filmmaking technique that did catch on was, of course, Tron’s use of computer-generated imagery, or CGI. Compared to what we are used to seeing these days, Tron’s 15 minutes of CGI doesn’t feel like much, but at the time it was a tremendous portion of a movie to be made on computer. We see it mostly in the landscapes, vehicles, and buildings in the computer world: the light cycles, the bad guy’s ship that’s totally an Imperial Cruiser, the solar sail gliding through those metal canyons. It’s not really computer animation as we think of it today; each frame was created individually and filmed by sticking a camera in front of the computer monitor. Four companies worked on the computer graphics, and they didn’t work together, so if you’re thinking that certain scenes look very different from other scenes, you are right.

You have by this point no doubt noticed that I’m focusing on how the movie got made, rather than on the content of the movie itself. The reason for that is, alas, I think the real-world, behind-the-scenes story is more interesting. It’s a film that took so many risks, achieved something that nobody else has ever done before or since, heralded so much technical innovation, and had such a lasting impact on how movies are made, but the movie itself is just kind of… fine. It’s fine. There’s some cool and tantalizing stuff in the story, but there’s also a lot that’s not very engaging.

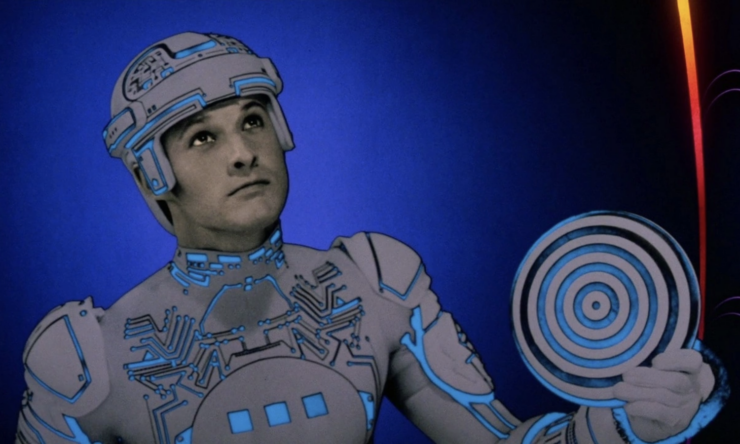

Tron tells the story of a computer programmer named Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges, clearly having a ball with the role) who used to work for a giant tech company called ENCOM. His former coworker at ENCOM, a man named Dillinger (David Warner), stole some video games created by Flynn and passed them off as his own. This includes a game called Space Paranoids, a fact that is not relevant to the movie’s plot in any way, I just want to mention it because Space Paranoids sounds like the absolute best video game. (Somebody apparently made it into a real game in 2010, but I don’t want to know about the real game. It’s never going to live up to what I imagine in my head.) Flynn now runs an arcade, where he regularly beats all of his customers on the games during his working hours, and during his downtime he tries to hack into the ENCOM mainframe to retrieve proof that Dillinger stole his work.

Dillinger, meanwhile, has risen to a position of power within ENCOM. Dillinger has developed the Master Control Program (MCP), a sinister artificial intelligence that is making itself stronger by subsuming all kinds of other computer programs, with the ultimate goal of—naturally—taking over the world. Two current ENCOM employees, Alan Bradley (Bruce Boxleitner, also known to sci fi fans as John Sheridan on Babylon 5) and Lora Baines (Cindy Morgan), suspect that Dillinger and his MCP are up to no good. They agree to help Flynn access the ENCOM system to find the proof he needs. The MCP has other ideas, however, and decides—in a delightful example of 1980s science fiction nonsense—to use a giant laser beam to dematerialize Flynn and trap him inside the ENCOM computers. (The laser laboratory in the movie is real: they filmed those scenes at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory.)

What Flynn finds inside the computer is an entire society. The MCP is a tyrant, various computer processes are his henchmen and underlings, and programs from elsewhere are captured and forced to fight to the death so that the MCP can gain more power. It’s all framed in a way that suggests and incorporates the way real computers work, which seems to have divided audiences at the time; some people loved it and some found it needlessly confusing. In addition, the programs have a distinctly religious view of their human creators and users, a belief the MCP wants to stamp out. That aspect is an interesting little bit of worldbuilding—humans did, after all, create the programs—but it’s not really explored in any depth and sometimes gives the film an uneven tone.

It’s not quite accurate to call this computer a virtual world, because it apparently exists as much in the hardware of the computer as in in the software, although narratively it serves much the same purpose. Lisberger was inspired by Alice in Wonderland, but my first thought upon watching is that this is classic isekai territory: a talented but unappreciated human guy is flung into a gamified world where his real-world skills give him an advantage over the locals.

What matters here is the spectacle—and it really is a spectacle. The light cycle race, the Frisbee battle, the chase scenes through weird and angular landscapes, villainous Sark (also David Warner) overseeing it all from his ship-that-is-not-an-Imperial-Cruiser-but-it’s-totally-an-Imperial-Cruiser, it’s all very cool to look at. One visual detail I really love is the parallel imagery between the computer world and how the real cityscape looks from the vantage of Dillinger’s office. The blending of gridworks of light and patterns of circuity across physical and electronic scales works very well here, and I think that’s in part because it’s such a clear-eyed look at how people were thinking about and visualizing technology at the time. (Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi also came out in 1982, so the ideas and visual themes were appearing in cinema all the way from the arthouse to the mainstream.)

Another thing I quite like is how in some ways the world operates on physical rules suited to this electronic scale (the light cycle beams and solar sail are two examples), but the tanks can still skid to a halt and topple off cliffs and characters can still cling to ledges in danger of falling. Because as much fun as the setting is, nobody actually wants to watch electrons chase each other around in a black box. Except particle physicists, I guess. My point is: the world can’t just look cool. It also has to feel like we could be there, isekai’d into it right alongside Flynn, and that balance between electromagnetic quirkiness and weighty Newtonian familiarity helps get us there.

In the end, all of that cinematic innovation is in service of a fairly fluffy story. Flynn helps Alan Bradley’s computer program Tron defeat the MCP, exactly as we expect. Flynn also gets credit for Space Paranoids and his other games and takes control of ENCOM, which is a very ’80s kind of happy ending. There’s never any doubt about how it’s going to end; it’s not the kind of movie that never opens up room for a darker conclusion. That’s not necessarily a problem; it’s actually fine for stories to show us where they intend to go, then go there. But in this particular case it does mean that while I was watching, part of my mind was always wondering what it would be like if it hadn’t been rewritten so many times, if there hadn’t been a push-and-pull during development over how lighthearted the film should be, what themes should be present, how the story and special effects would work together. According to a 2011 interview with Bonnie MacBird, I’m not the only one who reacts to the movie that way.

Whatever else it is, Tron is a movie people still discuss more than forty years later. I’ve talked before about the different ways a film can be the product of its time, and I think Tron is yet another example. There is something so very early ’80s computer age about the way it combines unabashed enthusiasm for how computers work with an approach to filmmaking that solves problems nobody else even thought about having. The love and excitement the film has for its subject matter really is apparent. It’s a film about computer nerds, for computer nerds, by computer nerds, in every possible way, and that’s a good thing.

I do, however, still maintain that it was a completely fucking insane way to make a movie. Don’t get me wrong: I’m glad they did it. But they were out of their minds.

One last note: I normally try to link major sources directly in the article, but there are many, many, many videos, articles, and interviews that get into the making of Tron, and I’ve drawn from several of them. Here are just a few that I looked at: Film School Rejects on the costuming, this YouTube video about backlight animation, a 1982 article in Video Games Player, a 1982 New York Times article about special effects in the movie industry, this Variety interview, and the documentary The Making of Tron.

What are your thoughts about Tron and all of the special effects work that went into making it? Did anybody watch it in theaters when it came out? I would love to hear about your response at the time! As is probably obvious, I have never watched Tron: Legacy, but I am curious so I likely will at some point.

Next week: Let’s bring virtual reality month to a close by meeting up in The Matrix and learning kung fu together. Watch it on Netflix, Max, Apple, Amazon, Google, Vudu, YouTube, and Microsoft.

Thank you for recognizing that TRON is not a virtual-reality movie as so many people (including the makers of TRON: Legacy) mistakenly assume it is. What’s inside the computer is not a visual representation for human eyes, it’s a magical world that humans have no idea is there until Flynn gets beamed inside it. The Programs aren’t player avatars, but literal computer programs that embody as miniature versions of their programmers because they’ve inherited some portion of their creators’ souls. It’s a complete fantasy take on how computers work, basically like Pixar’s Inside Out was for how the brain works. (It’s also much the same premise as ReBoot, the first fully CGI animated TV series.) Legacy got this wrong by portraying the Grid as a cyberspace simulation that Flynn intentionally created and populated with AIs.

Legacy got other things wrong as well. TRON was essentially an animated film in style and technique, despite the inclusion of live actors. The whole thing was about embracing the aesthetic of an artificial, simulated environment and trying to make the live actors look like part of it. Legacy was far more of a live-action film in look and style. While the original computer world consisted almost entirely of what we would now call virtual sets, Legacy made much more extensive use of real sets, which is ironic considering how much the technology for virtual sets has progressed. I just wasn’t convinced by the pretense that T:L’s world was a continuation of the world created in the original film. It was just too different in design and execution. It would’ve been truer to the original filmmakers’ intentions to do the Grid sequences fully in CGI, like the TRON: Uprising animated series did. The original film’s makers would’ve liked to do it that way, but the technology for animating CGI characters didn’t exist yet, which is why they had to employ such a complex hand-animation technique to try to make live-action performers look computer-animated.

Another thing T:L got wrong was the aesthetics of the Grid, all drab and gray with only two colors of illumination. Yeah, that was how the characters in the original looked due to the animation technology they used, but the Grid itself was vividly colorful, in a way characteristic of computer art in the 1980s. I once saw the makers of the original TRON talk about how the goals of computer animators had changed over time. In their day, when CGI was new, there was no hope of it replicating reality, so instead the focus was on embracing its unreality, exploring its potential for creating entirely new kinds of imagery impossible to create photographically. But once Jurassic Park showed that CGI could look realistic, that became the overriding goal, to match reality rather than transcending it. The original film’s makers regretted that change, and it’s manifested in how Legacy embraced physical sets and realistic CGI.

Then there’s the fact that T:L opens with Flynn’s son stealing Encom’s proprietary software and distributing it as freeware for everyone, alleging that that’s what his father would’ve wanted. But the original film’s Flynn had the exact opposite motivation: he wanted to prove that Dillinger had stolen his game designs so that he would get proper credit and compensation for his proprietary work. He was nothing if not a capitalist. So the discontinuity between the films exists on a character level as well as a design level. Either film works reasonably well by itself, as its own entity, but watch them back-to-back and the illusion that they represent a continuous reality is undermined.

Anyway, sorry to go on so much about the sequel’s shortcomings. But it underlines what you said about how unique the original film is. It’s a product of a particular, very brief window of time, and our perspective today is so different that it’s hard for modern audiences — or filmmakers — to understand what TRON was really trying to do.

Oh, yeah, that’s a good point I forgot to mention about the programs being a small part of their programmers–it adds a fun little twist to the religious aspect of the computer world!

That is so interesting about the sequel! I think I’m not surprised about the plot stuff, but I am surprised about the aesthetics, because the brilliant, changing, unpredictable colors and styles of the original are so important to it. And, yes, not at all trying to look realistic. I’m thinking of the scene where Flynn is wandering amongst some programs and it has this absolutely incredibly neon-meets-disco club vibe that simply could not exist in the real world.

Which is what I like most about the movie: it’s not trying to exist in the real world, it’s trying to put us into this strange, colorful, fantastical world with just enough familiarity that it feels real.

Rather, they didn’t want the fantastical world to feel real at all; they were trying to make real actors look as unreal as they could given the limitations of the available technology. CGI’s complete disconnect from physical reality was what made it intriguing, that potential to create entirely new kinds of imagery. The problem with TRON is simply that it was made a few years too early, before the technology existed to fulfill what the filmmakers had in mind.

One problem, for example, is that when the live-action footage was blown up onto individual animation cels to be backlit, altered, and reshot frame by frame, they didn’t take enough care to ensure that all the consecutive cels were from the same lot with the same film grain, so that gave the images a flickery quality they weren’t meant to have, because there were mismatches in the grain, exposure, or something along those lines from frame to frame.

This is one of my favorite movies! To the point that I’m making a tabletop roleplaying game that’s basically a Tron RPG with all the serial numbers filed off haha.

I can appreciate wanting more depth from the story. There was certainly space for addressing questions of theology, existentialism, and even transhumanism. It feels like there’s this giant hole where a third act shift should go that just isn’t there.

I’m glad you didn’t go into much detail about the sequel. I know some people like it but I feel like it was drained of basically everything that made the original fun and interesting. Tron is a fun watch because it’s a unique visualization of various computer concepts, what does a personified computer program look like? What does hacking look like in this universe? What does a server look like? These are are all opportunities for visually interesting set pieces, world-building, and computer based inside gags.

When I heard about the sequel I was excited! There have been a lot of changes to computers since the first one. What does a virus look like in the Tron universe? What does the internet look like? Tron: Legacy ignores all these excuses for visual splendor only to make a lifeless grimdark version of the first movie that vaguely gestures at profundity with no actually interesting ideas.

Maybe I just wanted Tron: Legacy to be Reboot with a budget haha.

Yes, your points on what makes this movie so interesting are exactly right! One thing I especially love is that all the characters accept without question that their programs can be sentient. There’s no waffling about around “how is this possible?” which opens up the story to simply run with it.

That’s so disappointing about the sequel, because there really IS so much that could be explored from the same approach.

Well, it is a Disney film. Anything can be sentient in the Disney ontology. Why not a computer program?

Yes, exactly. It’s sort of a spiritual antecedent of Wreck-It Ralph, except that the Programs aren’t actually game characters, just anthropomorphized applications (e.g. Tron is a security program, Clu is a hacking program, Peter Jurasik’s character is an accounting program, etc.). Or, as I mentioned, a technological equivalent of Inside Out or the sitcom Herman’s Head. It’s very much a fairy-tale version of how computers work, where there are little people inside performing the tasks.

When Wreck-It Ralph came out, my immediate reaction was that it was the real TRON sequel, the one I’d wanted all along.

It’s not a perfect analogy of course, just a gut feeling. But I love the shared idea that an individual can become more than what they were made for.

As a Canadian and a fan of certain indie movies, I think I am legally obliged at this point to say “Tron funkin’ blow”, even if I do not happen to hold that particular opinion (which I do not).

I don’t actually remember seeing TRON in its first theatrical run, but I think I did? But that’s also around the time that home video was becoming more widely available and I may have first seen it in that format.

It was also around the time that I was first learning about computers. I remember being quite infatuated with the idea of being able to directly experience them as a place rather than a thing. This may have primed me to become a fan of cyberpunk a few years later.

Yes, the concept of experiencing computers as a *place* is one aspect of the film that is so interesting and unique. There might be other examples of that approach in sci fi, but I can’t think of any. That’s part of why I think it’s so firmly grounded in the time it was made–it involves an inherent interest and enthusiasm regarding the working of computers that required a certain level of public familiarity with computers, but not so *much* familiarity that the general audience didn’t think about how they work anymore.

In some ways it made me think, a little bit, about one observed generation gap regarding computer usage. It’s often assumed that “older” people are the ones who don’t know to use computers, but a lot of people have observed that younger generations have become fairly computer helpless as well, because the user experience is so far removed from figuring out the nitty gritty details. Tron seems to sit right between those extremes and capture the “this is a strange new world, but we can figure it out” vibe that goes along with it.

TRON introduced young me to the concept of microcosms and macrocosms. I love the visual suggestions that the film’s “real world” is merely a larger computer world with its own grid patterns and flashing lights, suggesting planes of existence orders of magnitude beyond it, and by extension, beyond our own. “Greetings programs,” indeed…

“There might be other examples of that approach in sci fi, but I can’t think of any.”

As a couple of us have mentioned, Mainframe Animation’s ReBoot TV series was basically the same concept as TRON, focusing on characters who were programs inside a computer world represented as a fantastic city and landscape. They battled villains who were computer viruses, and they were periodically forced to play games imposed on their world against their will by an unseen, godlike User. I reviewed it on my blog a decade ago: https://christopherlbennett.wordpress.com/2014/12/29/more-old-sftv-reboot-spoilers/

Which indie movies? Never heard Canadians hating Tron (or much of anything…all nice and such)

If you search for the phrase, you’ll find the scene on YouTube. It comes from a film called FUBAR. In context, they are actually talking about a character in the film who is nicknamed “Tron”, rather than TRON the movie.

I highly recommend the making of TRON documentary that was on the DVD back in the day. Almost as good as the movie itself, I thought.

As for the sequel, I kind of dug it for what it was — that being a feature-length Daft Punk music video. I just wish Jeff Bridges had been allowed to go full Dude. Why so serious, Legacy?

I always say that the sequel has two things going for it – the music score and the DVD extras. Lots more Boxleitner in the extras! :-)

I did enjoy the Daft Punk score.

I get into arguments with Daft Punk fans over this. The LEGACY music may comprise a great dance album, but as a movie score I feel that it continually fights the rhythm of the film, flattening the action instead of complementing it.

“the movie itself is just kind of… fine.”

Yes. I saw it in the theater, and the visuals were mind-blowing, but I never really felt the need to go see it again. Probably caught it a couple times on cable years later.

The summer of 82 was just full of good (or fun) movies. I saw (in the theater) probably a third of the top 50 movies on this list:

https://www.boxofficemojo.com/season/summer/1982/

Some of them, ST:2, Poltergeist, Road Warrior, and Deathtrap, I saw multiple times in the theater and many others in heavy rotation on cable and VHS in later years. Trying to think of any other summer when two queer comedies like Victor/Victoria and Deathtrap were in the theaters at the same time.

It was truly a great year for movies–and several that I definitely want to cover in this column, because they cover such a range!

I don’t own a copy of ET but I own a copy of Tron. Possibly helped by the Intellivision Tron game this became one of my favorite movies after I saw it later in life. I was four in 82 so pretty sure I did not see it in theatre but man would I pay to do so now! Yes compared to the other movies you have discussed this is a fluff plot but it did have a corporate skull dudgery theme that predicted some of the 80s excesses.

We’re the same age and I had the same reaction to the corporate plot: oh, yes, we can see the heart of the ’80s corporate rot early on, right there. It’s fascinating in retrospect.

One thing I find interesting about the (flimsy) story of TRON is that Kevin Flynn is the main character, but Tron is the hero (and title character). It’s an unusual structure.

I definitely feel this film is a product of its time. As you pointed out, the film itself it just OK but those effects are truly unlike anything that has been done since then or before then. Also there was a quote about “computers being able to think for themselves” in the beginning of the movie that I couldn’t help but relate to the current surge in artificial intelligence. Finally, the way the film wraps up is way too campy for my tastes.

Except that so-called “AI” programs today aren’t thinking at all; that’s pure hype.

TRON isn’t a story about a computer (or program) achieving sentience. But if you like, it can be seen as a meditation on free will; when the programs ask Flynn if, as a user, he sees a greater plan to existence, he replies that he lives the same way they do, doing what it looks like he’s supposed to be doing. Are we humans actually thinking for ourselves, or merely performing our own more complex programming?

It’s not about programs achieving sentience because it presumes the programs already have sentience — in the same way Bambi presumes animals have sentience or The Brave Little Toaster presumes appliances have sentience. It’s an anthropomorphic fantasy for the computer age.

But at the same time it implies that the humans are no more sentient, as orders of magnitude go, than their programs are.

Yes, that’s just another way of saying what I said. Anthropomorphic fantasies portray nonhuman characters in a humanlike way for audience identification, whether it’s the talking animals in Watership Down or Chicken Run, the toys in Toy Story, the emotions in Inside Out, or whatever.

That’s external thinking, deconstructing the way movies are written. I was talking about the existential implications of the story, the internal logic.

Seeing Tron in the theatre when it was first released was mind blowing and the reason I got a Computer Graphics degree. It was and still is one of my favourite movies. Legacy, just like TRON, was more technology driven in its creation than you’d think. The colours of illumination were limited by the EL wire capabilities of the moment. The more prosaic embodied-ness of the characters due to the desire to use EL wire vs mocap dots. Imagine a TRON that uses post-Avatar 2 technology. Flynn’s open source idealism makes total sense to me and I don’t find it to be contradictory to his desire for credit/compensation in the original.

Olivia Wilde (Quorra) has become a director and expressed an interest in action films. I’d love for her to be handed the reins and create a sequel with more Bruce and maybe some Jeff in it, much more than the Leto/Ares that is bandied about.

“Flynn’s open source idealism makes total sense to me and I don’t find it to be contradictory to his desire for credit/compensation in the original.”

Between “Creators deserve to be paid for their work” and “Proprietary software should be bootlegged and given away for free?” I see a pretty blatant contradiction there.

Many programmers that work in open source, can eat and pay rent while contributing to open source because the companies they’re employed by compensate them for the work they do at their jobs.

IIRC from the novelization of Tron, Encom was a spreadsheet type company that branched out into games because that is logical corporate strategy. 8-) The sense that I got from Legacy, is that Flynn took over Encom but still had some spare time and instead of writing more games, both wrote FlynnOS and developed The Grid. Both were created for the betterment of society as a whole. Remember that ISOs were going to be his “gift to the world”.

After his disappearance, Encom appropriated and commercialized FlynnOS.

I still don’t see how that translates to Flynn being okay with stealing proprietary code and putting it out as a bootleg. That, IIRC, is what Flynn’s son does in Legacy, and it’s portrayed as being true to the ideals of his father. In other words, the original film’s Kevin Flynn was motivated entirely by defending his own property rights as the creator of the software, while Legacy claims that Flynn would support violating the property rights of other software creators/owners. And I’m not convinced that making the owners an evil corporation reconciles that contradiction.

is it really so hard to believe a corporate guy would evolve toward an open-source mindset over decades of time? Especially after he’s comfortably rich from due compensation?

Maybe not, but that’s not how Legacy portrayed it. It purported that Flynn had been a believer in open-source, free software from the beginning. It was going for nostalgia, after all, so it portrayed Flynn’s ideals as a continuation of who he’d been in the original film rather than a repudiation of it.

And it’s not about whether it can be factually rationalized. Stories aren’t just about cataloguing facts for wiki articles, they’re about feelings and impressions and tone. My point is that when I watched the two films back to back, they didn’t fit together well because there were so many differences in concept and approach. It’s not about whether it can be “explained,” it’s about whether it felt like an authentic continuation of the original. And it didn’t. It might have worked if I hadn’t managed to track down a library copy of the original and seen it the day before, if I’d had only my vague memories of the original film to go on. Then I might have found Legacy convincing as a continuation. But compared side by side, they’re a mismatched pair.

Speaking of, Chris, what do you think of TROn: Legacy as a film? On its own merits? Even putting aside the inconsistencies with its predecessor

Here’s my blog review from when it came out: https://christopherlbennett.wordpress.com/2011/01/19/tron-vs-tron-legacy-also-tangled/

My first introduction to Tron was the novelization of the movie (I think I may still have my original battered copy in a box in the attic). I subsequently saw the film itself, and have rewatched it once or twice since. I have read before about the process that the filmmakers used, but the description above was very helpful for understanding it, and for appreciating the full magnitude of the work involved. In addition, I was completely unaware of the history of backlit animation as used in traditional animated movies, so I appreciated the introduction to that as well.

I agree with ChristopherLBennett about Tron: Legacy; when I saw it, I was quite disappointed that it simply did not have the look and feel of the original Tron, especially where the characters were concerned. With regard to the changed nature of the computer world (the “Grid”), my impression at the time was that the makers of Tron: Legacy felt something along the lines of “Well, people know more about computers now, and audiences will never buy the idea that the computers that they use every day have a world of little people inside,” so they made the Grid something entirely separate from the Internet and the normal world of computing, something that Flynn had created that would work the way that the computer world of Tron worked. I agree that it takes away from the fantastic nature of the original, where the programs, as noted, are supposed to be actual programs, created in the image of their programmers (most notably in one of the clips above, where the character Ram explains that he is an actuarial program for an insurance company).

(The novelization includes some additional details, as well as a street scene with a variety of programs passing by, some of whom are not in fact anthropomorphic, which might have been interesting, but would have added additional complexity to the special effects,)

Oh, sure, I understand the reason for their updates to how they portrayed the computer world, at least in conceptual terms (though I still think the Grid scenes should’ve been full CGI animation rather than physical sets and drab photorealistic CG). Sometimes you have to update an old concept for a modern audience. I’m just saying that it creates a discontinuity, and that Legacy might be more enjoyable if you don’t watch it the day after rewatching the original film, as I did.

Funny how it’s one of two cyberspace-themed sequel/revivals I’m aware of that are actually undermined by familiarity with the original. The 2018 anime series SSSS.Gridman is a loose sequel to the 1993 live-action tokusatsu series Gridman the Hyper Agent, a cyberspace riff on the Ultraman format (and the basis of the American adaptation Superhuman Samurai Syber Squad, hence the anime title), but the anime’s plot is driven by the gradual unfolding of a mystery whose solution is immediately obvious to anyone familiar with the original show. So even though it’s very much an homage to the original and in some ways a direct continuation of it, its mystery element can only be fully enjoyed by people who know absolutely nothing about the original show and can share in the characters’ surprise at the gradual revelations of what’s going on. It was a very strange choice on the part of its creators.

A small note, but it irritates me that LEGACY brands the entire computer world as “The Grid,” when the gaming grid was a specific environment within the original film’s mainframe.